Scottish Pirates

SCOTTISH PIRATES-VICTIMS OF CIRCUMSTANCE OR PSYCHOTIC LUNATICS ?

So Here Are A Few Scottish Pirates

Not all pirates chose to be pirates..some thought they were actually doing quite a good job..Murdering,robbing,pillaging and defending their countries ,the problem with these guys was that they changed countries quite often, a lot depended on which country or on whose authority they had a license to steal for at any given point. On the whole they were a jolly bunch of chaps…But were they Buccaneers?

CAPTAIN WILLIAM KIDD

Buccaneers were so called because?

The original boucaniers were the native inhabitants of the West Indies who had developed a method of preserving meat by roasting it on a barbecue and curing it with smoke. Their fire pit and grating were called aboucan and the finished strips of meat were also known as boucan. In time, the motley collection of international refugees, escaped slaves, transported criminals and indentured servants who roamed along the coasts if the islands became known as buccaneers and the term came to describe an unscrupulous adventurer of the area.

But pirates on the other hand were more like this very early Orcadian ,Scottish ,Viking bampot

Thorbjorn Thorsteinsson

also known as Thorbjorn the Clerk,he was an Orcadian pirate who was executed in 1158.

Thorbjorn was married to the sister of Sweyn Asleifsson, but they first quarrelled after Sweyn attacked Thorbjorn’s cousin,Olvir Rosta, and grandmother, Frakkok, and burned her to death inside her house. Earl Rognvald Kali Kolsson forced a reconciliation, and the two went plundering together in the Hebrides, but fell out again over the distribution of the loot. Thorbjorn had his marriage annulled and entered Rognvald’s service.

Later, serving Harald Maddadsson, Thorbjorn found himself again thrown into Sweyn’s company.

In 1158, Thorbjorn was outlawed by Rognvald for murdering one of his retainers. He placed his faith in his friendship with Harald, but the two Earls had recently become allies, and Thorbjorn was in a very dangerous position. He attempted to resolve it by ambushing and assassinating Ranald; but Harald had him put to death.

Thorbjorn probably had some emotional problems ,being practically a pacifist during the Dark Ages was not normal,if he had only just murdered Harald or a few less members of his family and servants everything would have been hunkey -dorey ..sorted

Sir Andrew Barton

Was a jolly decent chap indeed

Privateer(c. 1466 – 2 August 1511) was a Scottish sailor from Leith, who served as High Admiral of the Kingdom of Scotland.

Some of Andrew Barton’s trading voyages to Flanders ports in the 1490s are recorded in the Ledger of Andrew Halyburton. He was the oldest of three brothers, a younger brother Robert Barton of Over Barnton became Lord High Treasurer of Scotland.

Andrew became notorious in England and Portugal as a ‘pirate’, though as a seaman who operated under the aegis of a letter of marque on behalf of the Scottish crown, he may be described as a privateer. The letter of marque against Portuguese shipping was originally granted to his father John Barton by James III of Scotland before 1485. John’s ships had been attacked by Portuguese vessels when he was trading at Sluis in Flanders.

James IV revived the letters in July 1507. When Andrew Barton, sailing in the Lion tried to take reprisals against Portuguese ships in 1508, he was detained by Dutch authorities at Veere. James IV had to write to Maximilian, the Holy Roman Emperor, and others to get him released in 1509. Andrew then took a Portuguese ship which carried an English cargo, leading to more difficulties, and James IV had to suspend the letter of marque for a year.Andrew captured a ship of Antwerp in 1509, the Fasterinsevin (the Shrove Tuesday), which did not come within his letter of marque. James IV ordered him to recompense the captain Peter Lempson and his officers for her cargo of woad and canvas.

The Bartons were in demand to support John, King of Denmark, and were allowed by him to harass the shipping of Lübeck. In return for this service, John of Denmark sent James IV timber for the masts of his ships from Flensburg. Andrew joined John’s service briefly in the spring of 1511, but sailed away without permission, also taking a ship that James IV had given to John.

Later in 1511, Andrew Barton was cruising the English coast looking for Portuguese prizes when he and his ships the Lion and Jenny Pirwyn were captured after a fierce battle with Sir Edward Howard and his brother Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, off Kent at the Downs. According to the story told in ballads, Andrew was subsequently beheaded. If true, such action would perhaps have been illegal because Barton possessed a letter of marque. Contemporary English and Scottish chronicle accounts agree that Andrew died of wounds received in the fight.

‘I am hurt but I am not slain.

I’ll lay me down and bleed awhile,

Then I’ll rise and fight again.’

“Red Legs” Greaves

was a Scottish buccaneer active in the Caribbean and the West Indies during the 1670s. His nickname came from the term Redlegs used to refer to the class of poor whites that lived on colonial Barbados some of whom took to wearing the Kilt for everyday attire,hence the red legs

Although considered a successful pirate during his career, most notably his raid of Margarita island in the mid-1670s, he is best known for his escape from Port Royal prison during an earthquake June 7, 1692.

Early life

Born in Barbados, Greaves’ parents had been tried for treason for their participation during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms and sold into slavery, as were many Royalists and Covenanters in Scotland. He is thought to have been born in 1649.

Born a short time after his parents’ arrival in Barbados, Greaves became the servant of a kindly master. However, his parents and master died a short time after another, and the orphaned boy was sold to another man who was claimed to have been violent and to have often beaten Greaves as a teenager.

Piratical career

During this time, concerned for his survival, he attempted to escape his servitude and successfully managed to swim across Carlisle Bay, stowing away on a ship preparing to leave Barbados. Although he assumed the vessel was a merchantship on its way to a far off port, the ship was actually a pirate ship commanded by a Captain Hawkins. Hawkins was known throughout the Caribbean as an unusually cruel pirate, often torturing captives, especially women, and rarely showing mercy to the crews of ships he attacked. Although feared by his crew, he was respected and very successful in capturing rich prizes.

After being discovered on board, Greaves was given the option of signing with the crew “offering the articles on a platter along with a pistol”. Although reluctant to join the crew under force, Greaves showed promise and quickly gained a reputation as a capable and efficient sailor.

However, he soon grew to resent and hate Captain Hawkins, both for being forced into his crew as for his distaste for brutality towards captured prisoners. The two eventually fought a duel, often claimed to be over the torture of a prisoner, although it is more likely Hawkins attacked Greaves for failing to obey his orders. During the fight, Greaves killed Hawkins and was elected by the crew to succeed Hawkins as captain.

Captain Greaves

Accepting their request, Greaves rewrote the Ship’s Articles, specifically prohibiting the mistreatment of prisoners and allowing the surrender of merchant captains during battle. Throughout the decade, Greaves found great success as well as gaining a reputation as an honorable captain widely known for his humane treatment of prisoners and never participating in the raiding of poor coastal villages.

Around 1675, he captured the island of Margarita, off the coast of Venezuela. After capturing the local Spanish fleet, he used their guns against the coastal defences and successfully stormed the town. After taking a large amount of pearls and gold, he soon left without looting the town, or harming the inhabitants.

Capture and escape

After the raid, Greaves was able to retire from piracy and settled down to the life of a gentleman farmer in Nevis. However, after being recognized by one of his former victims, he was turned in to authorities to collect the reward offered for his capture.

Greaves was found guilty of piracy and, despite his reputation, no leniency was shown towards him and he was sentenced to be hanged in chains. While imprisoned in the prison dungeon of Port Royal to await his execution, the town was submerged by an earthquake in 1692 with Greaves one of the few survivors eventually picked up by a whaling ship.

In gratitude, he joined the crew of the whaling ship and later became a pirate hunter, eventually earning a royal pardon for his efforts in the capture of a pirate ship which had been raiding local whaling fleets.

After his pardon, he again retired to a plantation and became known as a philanthropist in his later years, donating much of his wealth to various island charities and public works before his death of natural causes.

Alexander Dalzeel

(c. 1662 – December 5, 1715) was a seventeenth-century pirate and former officer under Henry Avery.

Born in Port Patrick, Scotland, Dalzeel went to sea as a child and, by the age of 23, was captain of his own ship with six successful voyages to his credit. Earning a reputation for dishonesty, Dalzeel arrived in Madagascar in 1685 and soon enlisted into the ranks of Captain Avery.

According to pirate lore, Dalzeel participated in the capture of the treasure ship Ganj-i-Sawai, which carried The Great Mogul’s daughter to her arranged marriage. Avery, who had decided to take her as his own wife, gave Dalzeel his own ship and crew within Avery’s fleet. Dalzeel would continue to serve under Avery until finally leaving for the West Indieson his own.

However, upon their arrival in the Caribbean, the pirates’ search for targets was fruitless. With their supplies slowly running short, starvation began to set in before a Spanish vessel was sighted. As the ship came into view, Dalzeel realized the Spanish ship was a well-armed Spanish war galleon which had presumably become separated from its escorts. Despite their ship’s smaller size, Dalzeel gave orders to close in on the ship.

Although the Spanish ship’s captain had been informed of the pirate ship’s presence earlier, he felt it too small to be a threat and retired to his cabin for a game of cards. As the ship approached the galleon, Dalzeel ordered a hole to be drilled in the side of his own ship so that his crew would be forced to fight to the death. Caught completely off guard, the Spaniards offered little resistance as Dalzeel’s crew boarded the galleon. Within minutes the ship was theirs and, storming into the captain’s quarters, they demanded his surrender at gunpoint.

After sailing his prize to Jamaica, Dalzeel was apprehended while attempting to capture a fleet of twelve Spanish pearl ships escorted by a Spanish man-o-war. In exchange for his surrender, Dalzeel and his crew were not forced into slavery or hard labor, as was common practice for captured pirates.

Released ashore, Dalzeel made his way back to Jamaica. There he began outfitting another ship and was soon sailing for Cuba. Again his outnumbered crew was captured by a Spanish naval patrol of three warships bound for Havana, where he was sentenced to be hanged at sea. Dalzeel, however, quickly made his escape after stabbing a guard and using two empty jugs to float to shore. Soon encountering another band of pirates, Dalzeel was able to convince them to attack and successfully capture the warship which had held him prisoner. As the pirates neared Jamaica, their ship sank in a sudden storm although Dalzeel was able to survive the storm in a canoe.

During the War of the Spanish Succession, Dalzeel was granted a commission by the French as a privateer. He enjoyed considerable success against British and allied nations before his eventual capture in 1712. Taken back to England, he was tried and convicted of treason and sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered. However, at the behest of the Earl of Mar, Dalzeel received a royal pardon and, upon his release, sailed for French waters, where he captured a French ship. He then had the captured crew’s necks tied to their heels and thrown overboard to watch them drown.

Eventually captured in Scotland, he was returned to London, where he was hanged on December 15, 1715.

And then there was

Captain William Kidd

(c. 22 January 1645 – 23 May 1701)

was a Scottish sailor who was tried and executed for piracy after returning from a voyage to the Indian Ocean. Some modern historians deem his piratical reputation unjust, as there is evidence that Kidd acted only as a privateer. Kidd’s fame springs largely from the sensational circumstances of his questioning before the English Parliament and the ensuing trial. His actual depredations on the high seas, whether piratical or not, were both less destructive and less lucrative than those of many other contemporary pirates and privateers.

Captain William Kidd was either one of the most notorious pirates in the history of the world, or one of its most unjustly vilified and prosecuted privateers, in an imperialistic age’s rationalisations of empire. Despite the legends and fiction surrounding this character, his actual career was punctuated by only a handful of skirmishes, followed by a desperate quest to clear his name.

Kidd was born in Dundee, Scotland, January 1645. He gave the city as his place of birth and said he was aged 41, in testimony under oath at the High Court of the Admiralty in October 1695 or 1694. Researcher Dr. David Dobson later identified his baptism documents from Dundee in 1645. His father was Captain John Kyd, who was lost at sea. A local society supported the family financially. Richard Zacks, in the biography The Pirate Hunter (2015), says Kidd came from Dundee. Reports that Kidd came from Greenock have been dismissed by Dr. Dobson, who found neither the name Kidd nor Kyd in baptismal records. The myth, that his “father was thought to have been a Church of Scotland minister”, is also discounted. There is no mention of the name in comprehensive Church of Scotland records for the period. A contrary view is presented here. Kidd later settled in the newly anglicized New York City. It was here that he befriended many prominent colonial citizens, including three governors. There is some information that suggests he was a seaman’s apprentice on a pirate ship, much earlier than his own more famous seagoing exploits.

By 1689 he was a member of a French-English pirate crew that sailed in the Caribbean. Kidd and other members of the crew mutinied, ousted the captain of the ship, and sailed to the British colony of Nevis. There they renamed the ship Blessed William. Kidd became captain, either the result of an election of the ship’s crew or because of appointment by Christopher Codrington, governor of the island of Nevis. Captain Kidd andBlessed William became part of a small fleet assembled by Codrington to defend Nevis from the French, with whom the English were at war. In either case, he must have been an experienced leader and sailor by that time. As the governor did not want to pay the sailors for their defensive services, he told them they could take their pay from the French. Kidd and his men attacked the French island of Mariegalante, destroyed the only town, and looted the area, gathering for themselves something around 2,000 pounds Sterling. During the War of the Grand Alliance, on orders from the provinces of New York and Massachusetts, Kidd captured an enemy privateer, which duty he was commissioned to perform,off the New England coast. Shortly thereafter, Kidd was awarded £150 for successful privateering in the Caribbean. One year later, Captain Robert Culliford, a notorious pirate, stole Kidd’s ship while he was ashore at Antigua in the West Indies. In 1695, William III of England replaced the corrupt governor Benjamin Fletcher, known for accepting bribes of one hundred dollars to allow illegal trading of pirate loot, with Richard Coote, Earl of Bellomont.[5] In New York City, Kidd was active in the building of Trinity Church, New York.

On 16 May 1691, Kidd married Sarah Bradley Cox Oort, an English woman in her early twenties, who had already been twice widowed and was one of the wealthiest women in New York, largely because of her inheritance from her first husband.

Hunting for pirates

In September 1696, Kidd weighed anchor and set course for the Cape of Good Hope. A third of his crew soon perished on the Comoros due to an outbreak of cholera, the brand-new ship developed many leaks, and he failed to find the pirates he expected to encounter off Madagascar. Kidd then sailed to the Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb at the southern entrance of the Red Sea, one of the most popular haunts of rovers on the Pirate Round. Here, he again failed to find any pirates. According to Edward Barlow, a captain employed by the English East India Company, Kidd attacked a Mughal convoy under escort by Barlow’s East Indiaman, and was repelled. If the report is true, this marked Kidd’s first foray into piracy.

As it became obvious that his ambitious enterprise was failing, Kidd became understandably desperate to cover its costs. But, once again, he failed to attack several ships when given a chance, including a Dutchman and a New York privateer. Some of the crew deserted Kidd the next time Adventure Galley anchored offshore, and those who decided to stay on made constant open-threats of mutiny.

Kidd killed one of his own crewmen on 30 October 1697. While Kidd’s gunner, William Moore, was on deck sharpening a chisel, a Dutch ship appeared in sight. Moore urged Kidd to attack the Dutchman, an act not only piratical but also certain to anger the Dutch-born King William. Kidd refused, calling Moore a lousy dog. Moore retorted, “If I am a lousy dog, you have made me so; you have brought me to ruin and many more.” Kidd snatched up and heaved an ironbound bucket at Moore. Moore fell to the deck with a fractured skull and died the following day.

While seventeenth-century English admiralty law allowed captains great leeway in using violence against their crew, outright murder was not permitted. But Kidd seemed unconcerned, later explaining to his surgeon that he had “good friends in England, that will bring me off for that.”

Accusations of piracy

Acts of savagery on Kidd’s part were reported by escaped prisoners, who told stories of being hoisted up by the arms and drubbed with a drawn cutlass. On one occasion, crew members ransacked the trading ship Maryand tortured several of its crew members while Kidd and the other captain, Thomas Parker, conversed privately in Kidd’s cabin. When Kidd found out what had happened, he was outraged and forced his men to return most of the stolen property.

Kidd was declared a pirate very early in his voyage by a Royal Navy officer, to whom he had promised “thirty men or so”. Kidd sailed away during the night to preserve his crew, rather than subject them to Royal Navy impressment.

On 30 January 1698, he raised French colours and took his greatest prize, an Armenian ship, the 400-tonQuedagh Merchant, which was loaded with satins, muslins, gold, silver, an incredible variety of East Indian merchandise, as well as extremely valuable silks. The captain of Quedagh Merchant was an Englishman named Wright, who had purchased passes from the French East India Company promising him the protection of the French Crown. After realising the captain of the taken vessel was an Englishman, Kidd tried to persuade his crew to return the ship to its owners, but they refused, claiming that their prey was perfectly legal, as Kidd was commissioned to take French ships, and that an Armenian ship counted as French, if it had French passes. In an attempt to maintain his tenuous control over his crew, Kidd relented and kept the prize. When this news reached England, it confirmed Kidd’s reputation as a pirate, and various naval commanders were ordered to “pursue and seize the said Kidd and his accomplices” for the “notorious piracies” they had committed.

Kidd kept the French passes of Quedagh Merchant, as well as the vessel itself. While the passes were at best a dubious defence of his capture, British admiralty and vice-admiralty courts (especially in North America) heretofore had often winked at privateers’ excesses into piracy, and Kidd may have been hoping that the passes would provide the legal fig leaf that would allow him to keepQuedagh Merchant and her cargo. Renaming the seized merchantman Adventure Prize, he set sail for Madagascar.

On 1 April 1698, Kidd reached Madagascar. Here he found the first pirate of his voyage, Robert Culliford (the same man who had stolen Kidd’s ship years before), and his crew aboard Mocha Frigate. Two contradictory accounts exist of how Kidd reacted to his encounter with Culliford. According to The General History of the Pirates, published more than 25 years after the event by an author whose very identity remains in dispute, Kidd made peaceful overtures to Culliford: he “drank their Captain’s health,” swearing that “he was in every respect their Brother,” and gave Culliford “a Present of an Anchor and some Guns.” This account appears to be based on the testimony of Kidd’s crewmen Joseph Palmer and Robert Bradinham at his trial. The other version was presented by Richard Zacks in his 2002 book The Pirate Hunter: The True Story of Captain Kidd. According to Zacks, Kidd was unaware that Culliford had only about 20 crew with him, and felt ill manned and ill equipped to take Mocha Frigate until his two prize ships and crews arrived, so he decided not to molest Culliford until these reinforcements came. After Adventure Prize andRouparelle came in, Kidd ordered his crew to attack Culliford’sMocha Frigate. However, his crew, despite their previous eagerness to seize any available prize, refused to attack Culliford and threatened instead to shoot Kidd. Zacks does not refer to any source for his version of events.

Both accounts agree that most of Kidd’s men now abandoned him for Culliford. Only 13 remained withAdventure Galley. Deciding to return home, Kidd left theAdventure Galley behind, ordering her to be burnt because she had become worm-eaten and leaky. Before burning the ship, he was able to salvage every last scrap of metal, such as hinges. With the loyal remnant of his crew, he returned to the Caribbean aboard theAdventure Prize.

Trial and execution

Prior to returning to New York City, Kidd learned that he was a wanted pirate, and that several English men-of-war were searching for him. Realizing that Adventure Prize was a marked vessel, he cached it in the Caribbean Sea and continued toward New York aboard a sloop. He deposited some of his treasure on Gardiners Island, hoping to use his knowledge of its location as a bargaining tool. Kidd found himself in Oyster Bay, as a way of avoiding his mutinous crew who gathered in New York. In order to avoid them, Kidd sailed 120 miles around the eastern tip of Long Island, and then doubled back 90 miles along the Sound to Oyster Bay. He felt this was a safer passage than the highly trafficked Narrows between Staten Island and Brooklyn.

Bellomont (an investor) was away in Boston, Massachusetts. Aware of the accusations against Kidd, Bellomont was justifiably afraid of being implicated in piracy himself, and knew that presenting Kidd to England in chains was his best chance to save himself. He lured Kidd into Boston with false promises of clemency, then ordered him arrested on 6 July 1699. Kidd was placed in Stone Prison, spending most of the time in solitary confinement. His wife, Sarah, was also imprisoned. The conditions of Kidd’s imprisonment were extremely harsh, and appear to have driven him at least temporarily insane. By then, Bellomont had turned against Kidd and other pirates, writing that the inhabitants of Long Island were “a lawless and unruly people” protecting pirates who had “settled among them.”.

He was eventually (after over a year) sent to England for questioning by Parliament. The new Tory ministry hoped to use Kidd as a tool to discredit the Whigs who had backed him, but Kidd refused to name names, naively confident his patrons would reward his loyalty by interceding on his behalf. There is speculation that he probably would have been spared had he talked. Finding Kidd politically useless, the Tory leaders sent him to stand trial before the High Court of Admiralty in London, for the charges of piracy on high seas and the murder of William Moore. Whilst awaiting trial, Kidd was confined in the infamous Newgate Prison, and wrote several letters to King William requesting clemency.

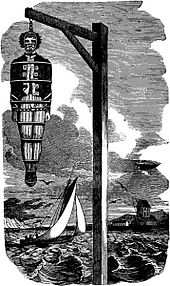

Kidd had two lawyers to assist in his defence. He was shocked to learn at his trial that he was charged with murder. He was found guilty on all charges (murder and five counts of piracy). He was hanged on 23 May 1701, at ‘Execution Dock’, Wapping, in London. During the execution, the hangman’s rope broke and Kidd was hanged on the second attempt. His body was gibbeted over the River Thames at Tilbury Point—as a warning to future would-be pirates—for three years.

His associates Richard Barleycorn, Robert Lamley, William Jenkins, Gabriel Loffe, Able Owens, and Hugh Parrot were also convicted, but pardoned just prior to hanging at Execution Dock.

Kidd’s Whig backers were embarrassed by his trial. Far from rewarding his loyalty, they participated in the effort to convict him by depriving him of the money and information which might have provided him with some legal defence. In particular, the two sets of French passes he had kept were missing at his trial. These passes (and others dated 1700) resurfaced in the early twentieth century, misfiled with other government papers in a London building. These passes call the extent of Kidd’s guilt into question. Along with the papers, many goods were brought from the ships and soon auctioned off as “pirate plunder.” They were never mentioned in the trial.

As to the accusations of murdering Moore, on this he was mostly sunk on the testimony of the two former crew members, Palmer and Bradinham, who testified against him in exchange for pardons. A deposition Palmer gave, when he was captured in Rhode Island two years earlier, contradicted his testimony and may have supported Kidd’s assertions, but Kidd was unable to obtain the deposition.

A broadside song Captain Kidd’s Farewell to the Seas, or, the Famous Pirate’s Lament was printed shortly after his execution and popularised the common belief that Kidd had confessed to the charges.